|

WILL THE AMAZON RAINFOREST HELP IN TAKING UP 200404

1. PHOTOSYNTHESIS VS. RESPIRATION

Through photosynthesis, all forests take carbon dioxide from the air and incorporate

the carbon molecule into organic matter.

In tropical rainforests such as the Amazon, great quantities of carbon

are fixed daily into cellulose, lignins, and other natural compounds

to become part of the biosphere.

This fact has encouraged the argument that the

preservation of the Amazon rainforest will ensure

the removal of the excess carbon that has accumulated

in the atmosphere over the past 50 years due to the burning of fossil fuels. At issue is the

carbon flux entering the forest, i.e., the daily production of vegetative matter,

not the carbon matter stored in the tree stands through millennia.

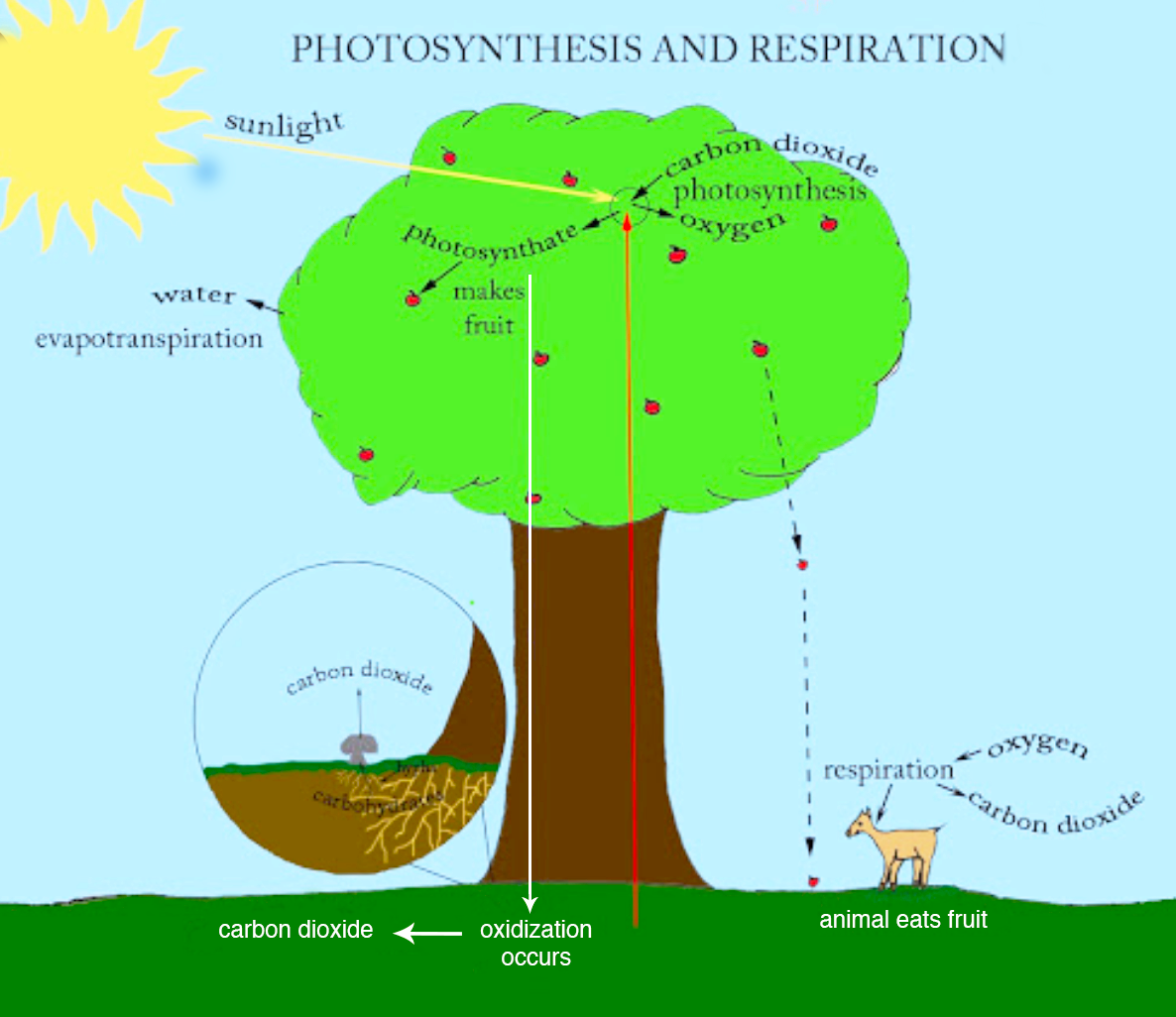

Fig. 1 Photosynthesis and respiration. The fallacy of this argument is apparent when it is recognized that photosynthesis does not act alone. In nature, photosynthesis is intrinsically coupled with the biochemically opposite process of respiration. Photosynthesis reduces the amount of carbon in the air, while respiration increases it. For any ecosystem, a mass balance may be stated as follows:

In tropical rainforests, gross production (i.e., the amount of photosynthesis) and respiration take place at about the same rate. In many cases, the amount of respiration is very close to that of gross production, resulting in net production being very near zero. The high rates of respiration are a result of the well developed food chains, which promote efficient biodegradation and fast nutrient recycling. The soils of the Amazon rainforest have been heavily leached through millennia by abundant rainfall and, are, therefore, generally poor in nutrients. The system's nutrients are stored in the canopy, with fast nutrient recycling being the rule. Therefore, a rainforest is likely to sequester very little carbon. Through efficient food chains, the organic matter biodegrades quickly, the nutrients are recycled promptly, and the carbon dioxide is released back to the atmosphere almost as fast as it is uptaken. Thus, the Amazon and other tropical rainforests are not likely to help in removing excess carbon from the air.

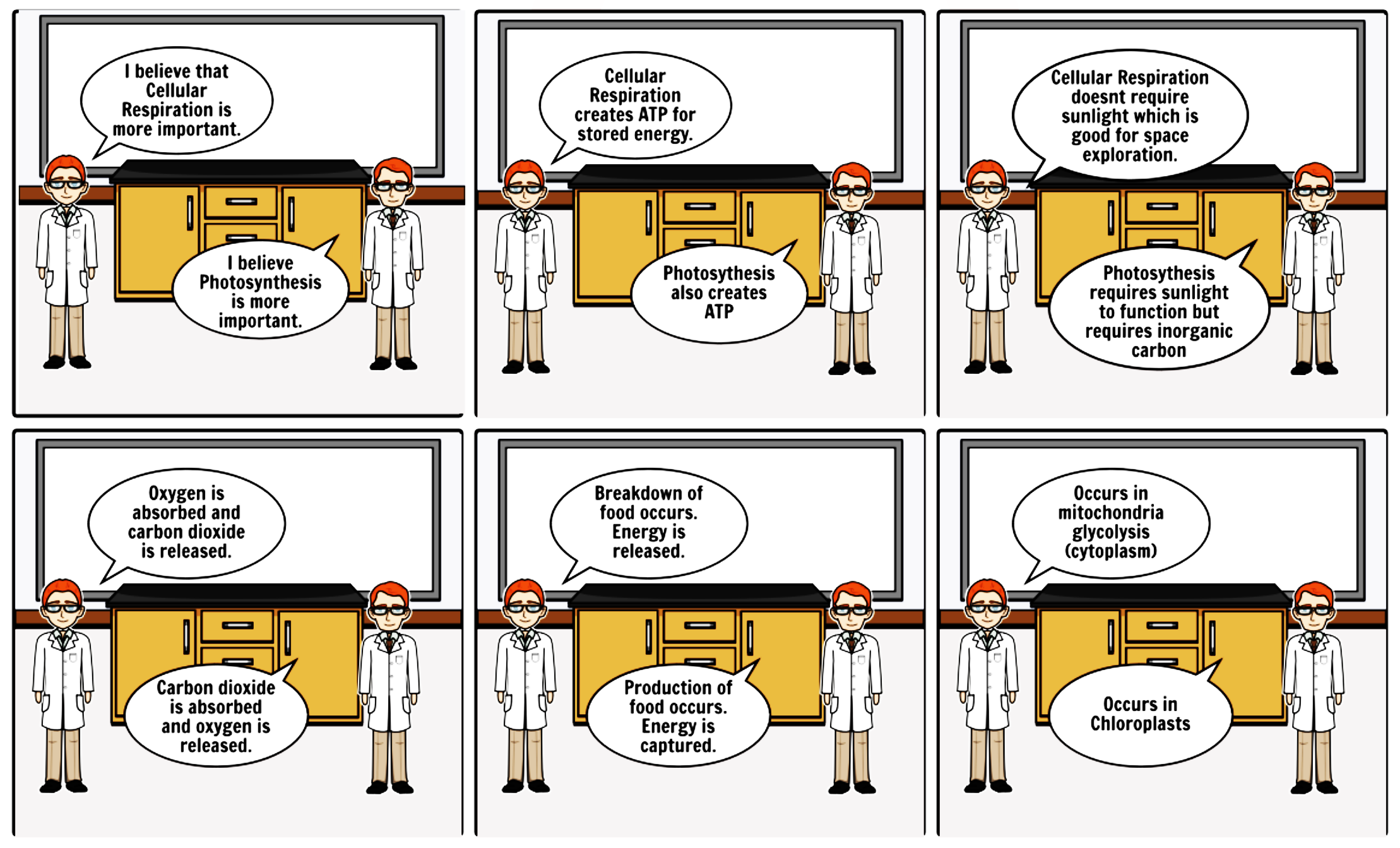

Fig. 2 Photosynthesis vs. respiration.

2. A MEANINGFUL OBSERVATION

The observation of Nature leads to the formulation of natural laws.

A fundamental law is that of action and reaction; there is no action

without a reaction. Another basic law is the law of scale: Scale matters

in all natural processes. A meaningful observation

may be drawn from comparison of the climatic precipitation

range (arid vs. humid) with the spectrum of shallow waves in open-channel flow. In the latter

case, the range is from kinematic waves on the

left side of the scale to dynamic waves on the right side

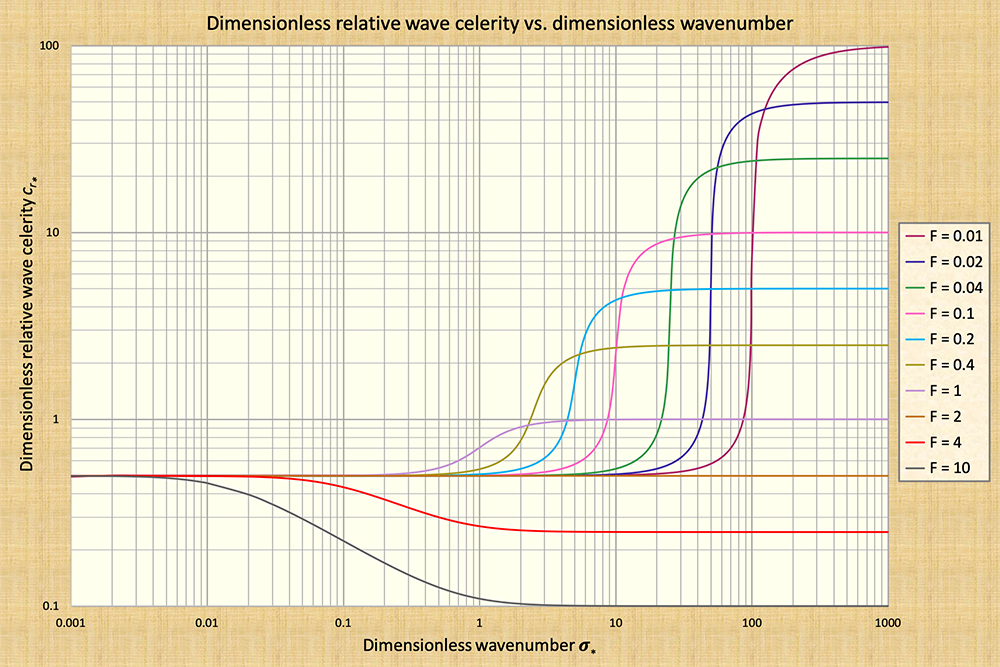

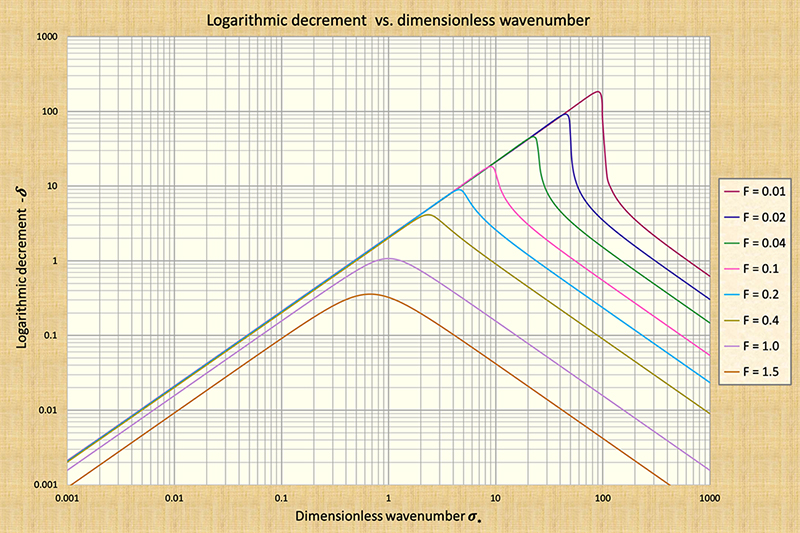

Fig. 3 Celerity of shallow waves in open-channel flow. The difference in wave behavior is given by the attenuation, or decay. Wave attenuation peaks around the middle of the wavenumber spectrum, reducing to zero at both extremes (Fig. 4). A similar phenomenon may be observed in the climatic precipitation spectrum. Deserts, with scarce rainfall, feature little biomass production and, consequently, a scant food web and small amounts of respiration. Conversely, rainforests, with huge quantities of rainfall, have a lot of biomass production and, consequently, a well developed food web and very significant amounts of respiration. Under this view, neither deserts nor rainforests are likely to have substantial amounts of net ecosystem production.

Only in the middle of the climatic precipitation

spectrum, at the average terrestrial value, i.e.,

close to

Fig. 4 Attenuation of shallow waves in stable open-channel flow.

3. EPILOGUE

The utility of the rainforest is not in helping to remove the contemporary industrial carbon from the air.

REFERENCES

Ponce, V. M. and D. B. Simons. 1977.

Shallow wave propagation

in open channel flow. Journal of the Hydraulics Division, ASCE, Vol. 103, No. HY12, December, 1461-1476.

|

| 200406 07:00 |